|

By Wu Hung

Transience, Chinese Experimental Art at the End of the Twentieth Century,

1999, Published by The Smart Art Museum, Chicago, USA

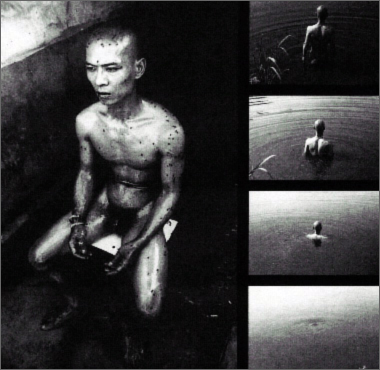

12 Square Meters, 1994, Performance, Beijing

Speaking the Unspeakable

Rong Rong, who photographed the still shots of Zhang Huan’s 12 Square Meters, wrote the following letter to his sister on June 3, 1994, the day after Zhang’s action project took place:

Younger Sister:

What’s going on here is just unthinkable. Let me tell you why.

We were planning an action project. Zhang chose to do this piece of work in a public toilet in the Village (the dirtiest and smelliest in the world). This is what he was going to do: He would place himself in the middle of the loo, naked, with some foul-smelling substance and honey covering his body. As a result, a swarm of innumerable flies would stick to his body. He would sit still for an hour.

At 11:30 am yesterday, Zhang began this while (Our friends) Curse, Ma, and Terror were witnessing the whole event. We even had a man with a video camera on the scene. Terror spread the stuff on Zhang’s body. In no time at all flies were attracted. I had a rag to cover my mouth and nose (quite like a gas mask). You know how it stinks in the loos here, and the temperature then was F 100. The bugs soon covered Zhang’s body, his face, penetrated his nostrils and ears. Everything was so still, one could only hear flies flapping their wings and my camera clicking.

The new (of what we were doing) then got out and led to a public outcry. After Zhang had finished he stepped into a small pond behind the toilet. Lots of dead flies floated on the water, moving slightly with the smooth circular waves around Zhang’s straight body. Zhang called the whole thing 12 Square Meters, which is of course the size of the public loo. He said that the squalid condition of the toilet and the army of flies in it gave him the inspiration. Some local "Villagers" voiced their concerns by calling what we did yesterday pornographic.

(Cited from Rong Rong’s unpublished letter. This translation is based on an English version provided by the artist to the author.)

The village, the location of the public toilet and the site of Zhang’s performance, stands for the "East Village," (Dong Cun) a garbage-filled district in the east side of Beijing. Mainly because it provided some of the cheapest housing in the city, it had become home to budding performance and action artists by 1993. Zhang Huan was among the earliest members of this artistic community. When he moved there in 1992 he was still registered as a student in the Oil Painting Department in the Central Academy of Art. But moving into the Village marked an entirely new beginning in his artistic life.

Born in a worker’s family in Anyang, Henan province, Zhang Huan spent his childhood in the countryside. Although he received some poor grades in humanities and science courses (which he attributes to his "backward" background), his artistic talent was recognized even in the elementary school. In high school he spent hours and hours painting plaster statues and still life. After graduating from high school he applied to the Art Department of Henan Provincial University, but was able to pass the entry exams only after two failed attempts. In college he found his artistic ideal in Jean-Francois Millet’s portrayals of ordinary lives, painting in which humble people radiate classical beauty. The most serious work Zhang Huan made under such influence was his graduation painting Red Cherries (1988), which depicts a mother peacefully nursing her baby with a bowl of cherries nearby. This penchant for classical beauty persisted when he advanced to a two-year training program in the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which attracted him mainly because of its strong emphasis on the European classical tradition. The director of the academy, Jin Shangyi, has been Zhang’s hero for many years. Jin’s portraits and nudes from the 1980s and early 1990s integrated French academic influence with Russian realism, with the self-confessed goals of emotional balance and technical perfection.

Nothing in Zhang Huan’s life before he reached age 27, then, seems to have prepared him for his sudden change in 1992: he abandoned the noble art of oil painting and began to stage the series of violent and masochistic performances that have become his trademark. He seems unsure about the reasons for this drastic change. When I asked him what caused him to turn against classic art, he pondered the question and then said, rather unexpectedly:

Maybe it was because of the poor countryside in Henan where I grew up. There everything was colored by the yellow earth. I got hepatitis--because I had nothing to eat. There were many deaths and funerals. I can never forget the funerals of my grandmother (who raised Zhang Huan) and other relatives. Maybe it was also because of my personal life in Beijing. You could not keep your child when your girlfriend was pregnant--Girls of my generation have to go through many abortions; some have done it twice or three times, some five or six times. Many unborn babies died. This is the situation of the nineties. I am not clear about the seventies and eighties. But I know my own generation of people well. My first performance was called Weeping Angels.

(Interview with Zhang Huan conducted by the author. July 13, 1998. Unpublished record. This performance was staged in Beijing’s National Art Gallery on October 26,1993. Zhang Huan first unwrapped layers of black clothes to expose an urn and poured the bloodlike paint in the urn over his own head. The urn fell and broke; fragments of a plastic baby, originally placed in the urn, were scattered on the ground and mixed with the red paint. Finally, Zhang, who was basically naked, brought the broken plastic baby into the gallery and hung it on a string against a black canvas on the wall.)

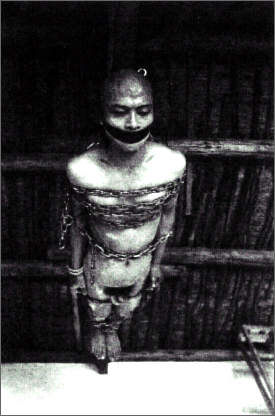

65KG, 1994, Performance, Beijing

The two different experiences mentioned here are apparently connected by death, and one can find solid ground for interpretation of Zhang Huan’s art by linking his masochistic actions with his guilt toward the dead. The performance Weeping Angels (1993), which involved symbolic abortion and death, was related to his installations of broken baby dolls. Almost every performance he has undertaken since then simulates self-sacrifice. In some of these projects he offers his flesh and blood; in other projects he tries to experience death, either locking himself inside a coffinlike metal case or placing earthworms in his mouth and allowing them to escape. It is equally important, however, to realize that to Zhang Huan "death" has another meaning, manifested not in human lives but in the social environment. These are places of death that I have termed "wastelands": abandoned public spaces filled with refuse; graveyards of dead things that resist quick disintegrations; sources of polluted food and water as well as poisonous fumes and smells; "black holes" in an urban or rural landscape that absorb time and escape change. Differing from ruins of a classical monument, these wastelands contain no "fragments from which we try to reconstruct the lost totality." Such a place does not inspire sentiment or stir up memory. Instead it is a contagious corpse that suffocates people with its deadly excrement. The masochism in Zhang Huan’s performances often forces him to experience such a space or to reduce himself to part of it.

From this point of view, his moving into the tumbledown East Village was already an act of self-exile. Karen Smith, a writer and art critic based in Beijing, records the village’s environment in the early nineties:" In the shadow of the metropolis, many of the village’s indigenous population scrape a living by collecting and sorting rubbish. Waste accumulates by the side of the small ponds. This pollutes the water, generating noxious fumes in the summer. Raw sewage flows directly into the water. Slothful, threadbare dogs roam the narrow lanes between houses. People stare with the blankness of the illiterate and benighted. As I will discuss later in the essay on Rong Rong, another member of the village’s artistic community, the artists living there were fully conscious of the hellish qualities of the place in contrast to the "heavenly" downtown Beijing. This contrast energized them, however, for they and their art were also condemned as "garbage" and "hellish," even by other experimental artists.

This ambivalence toward the place and themselves is best captured by Zhang Huan’s 12 Square Meters, described by Rong Rong at the beginning of this essay and shown in a video in this exhibition. On the one hand, by subjecting himself to an unbearably filthy public toilet for an hour, Zhang identifies himself with this place and embraces it. On the other hand, he was clearly suffering during the whole ordeal while struggling to keep his composure in the inhuman environment. He says in a "self-statement" that this project allowed him "to experience his essential existence" reduced to the level of waste. But the same "self-statement" links his own existence to a general "relationship between people and their environment" in contemporary China, where numerous public toilets in similar conditions continue to exist in large and small cities and towns, hidden in dark alleys in the most densely populated areas and in the shadow of glamorous skyscrapers. It is in this sense that Zhang Huan’s 12 Square Meters combines personal experience with a social critique--two essential elements of his performance art. |