|

By Luna Shyr

Art + Auction, Dec. 2007, The Power Issue, USA

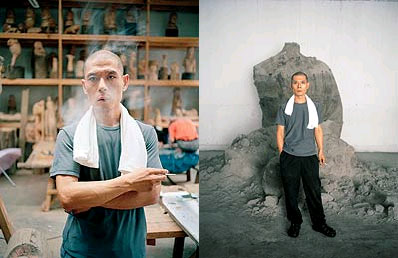

Photo by Daniel Traub

In the Studio: Zhang Huan

"Now based in Shanghai, the artist has traded in his shocking performances for grand objects that honor Chinese culture."

Zhang Huan has discovered a different kind of Nirvana. Back in the mid-1990s, it was the Seattle grunge band of that name that inspired him as an impoverished Beijing-based performance artist. The work he produced, like the music he listened to, was subversive: He slathered his body with honey and fish oil to attract flies in a public toilet and, in another piece, encased his naked torso in the rib cages of pig carcasses from a local market. Each performance was a testimony of personal experience, whether testing his ability to endure pain or measuring himself against a pond or a mountain.

A less evident influence at the time was the Buddhist temple music he also favored. “I had no idea what the rockers were singing about. I didn’t know what the Buddhist music was about either, but I liked the melodies a lot,” Zhang recently told an audience at the Asia Society in New York, where a retrospective of his work is on view through January 20.

As several new sculptures in the show make clear, Buddhism has emerged as a prevalent theme in the artist’s work. A giant copper arm, Fresh Open Buddha Hand, lies with deceptive lightness across one gallery, the palm of the hand split open. In another room, a massive head made of incense ash and steel, Long Ear Ash Head, melds the artist’s image with the elongated earlobes that represent joy and good fortune in the Buddhist religion. Gone are the angst and confrontation so characteristic of Zhang’s performances. In their place are art objects infused with serenity and a reverence for Chinese tradition and history.

The 42-year-old artist attributes the shift in his sensibility to the mellowing effect of growing older, but Zhang is not a man content to stay still. He appears to have barely aged since he pulled and pinched his face in Skin a decade ago. His gaze is steady and direct. And his toned, compact body, often nude in his performance art, moves with deliberate grace. This outward stillness belies a mind that is in constant motion, rich with ideas and ambition. “My brain is my studio,” he says. If that’s the case, his brain takes up some 75,000 square feet of industrial space.

The day I arrive at his studio in Xin Zhuang, about an hour’s drive from Shanghai, torrential rains are saturating the area. Water drips through the roof of various workshops housed in a cavernous shed formerly occupied by a Japanese clothing factory. Zhang took over the site in 2006, after a fire gutted the company’s operations. “In China, it’s believed that once you move into a place that’s burned,” explains our translator, “your business will catch fire.”

This has certainly been true for Zhang, although his career momentum had been building for a decade. His performance pieces brought him attention in the late 1990s from P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center and the Asia Society, both in New York; a move to that city followed, as did performances in the U.S., Europe and Australia. His timing was impeccable: As contemporary Chinese artists became the talk of the art world, Zhang was well positioned to translate critical attention into commercial success. After eight years in New York, however, he no longer felt it was the perfect city he had envisioned dg hng his Beijing days. He was also growing tired of performance art.

Zhang says it was fate that brought him to Shanghai. A fortune teller told him that a suitable place for his next move would be in eastern China or somewhere northeast of his birthplace, in the Henan province. Once settled in Shanghai, and aided by an average of 100 assistants, he quickly started producing the ash paintings, copper sculptures, woodcut prints and “Memory Door” series of carved portals that define his most recent body of work. This fall, in addition to the Asia Society show, Zhang’s richly textured ash paintings and sculptures were exhibited at Haunch of Venison in London and Berlin. The artist has also signed on with PaceWildenstein, in New York, which plans to hold an exhibition of his work in its two downtown spaces in May 2008. Pace founder Arne Glimcher was so taken with Zhang’s studio that its spirit will be transported to New York during the show, when several of the artist’s wood-carvers will set up shop in the gallery. Glimcher calls Zhang “a force of nature, the likes of which I’ve only seen a couple of times before.”

When Zhang and I enter the printing workshop, two assistants are asleep atop a stack of wood slabs the size of a parking space. The naps are sanctioned; the studio goes into sleep mode between noon and 1 p.m., when lunch is served on metal trays. (Running a large studio has its challenges: Despite the presence of two in-house chefs, Zhang says, the staff is complaining that they’re bored with the food.) It isn’t long before the sound of rocks being rubbed over carved wood—a traditional Chinese printing method—echoes in the workshop.

Similarly, the “Memory Door” workshop goes quickly from silence to a cacophony of hammering as some dozen assistants set to work on antique wood portals collected from the Shanxi province. Mounted on each door are silkscreens of black-and-white photographs depicting historical scenes of daily life in China. Parts of the pictures are sculpted into the wood. Zhang points out how much more detailed the carved portion of one panel is than the grainy photograph attached to it: In the photo the leaping fish are mere shadows; in the carving they have scales and lips. “There are two different worlds here,” he says. “Something from reality and something from imagination.”

Zhang himself seems to thrive in two different spheres. His production setup, schedule of visitors (he mentions a Rothschild family member and Glenn Lowry, director of New York’s Museum of Modern Art) and accessibility to the press suggest an acute businessman. Then there is the philosopher and creator. “I’ve thought about stopping and dropping everything, but I will still age and die,” he says, inhaling a steady stream of superslim cigarettes. “I can put out all my ideas and make all this work with enthusiasm while I’m still alive. When you’re really involved in your work, you don’t have time to contemplate other things, such as basic living conditions and the meaning of life.”

It might be those kinds of matters that weigh on Zhang during what he calls the most intolerable moments of his day: the few minutes when he is just waking up from his lunchtime nap. This he takes underneath his desk, in a roughly two-foot-high space outfitted with a mattress, pillow, sheets and comforter. “I feel safe on a low level. It quiets me down,” he says. The bed in the Shanghai home he shares with his wife and two young children is simple as well.

For all his success, Zhang hasn’t shaken the memories of his less fortunate days, when he struggled with money, school and, one suspects, social convention. In one of the workshops—toward the back of the shed near a barking German shepherd—a stuffed cow hangs impaled on a pole, its head wrapped in a white cloth, over a bucket. Henan Bull No. 2 relates to an incident from his youth when two men in a bar smashed his face with beer bottles and he found himself in the hospital, head swathed in bandages, without money. For Zhang, art remains a way of expressing his memories and identity. His latest creative vocabulary—ash, historical images, Buddhist sculpture—reflects the inspiration of old Chinese materials and objects that he rediscovered upon returning to his homeland.

A short drive away, in another industrial warehouse, workers are variously welding metal, splitting a huge tire and constructing what will be a massive, 12-foot-high wood cylinder of Chinese medicine drawers. One wedge of the wheel, which will ultimately be some 30 feet in diameter and consist of 6,080 drawers, appears complete. Zhang pulls out a drawer big enough to comfortably hold a baby or two, and says he hasn’t yet decided what to fill the compartments with. Traditionally, they are tiny and hold herbal remedies. In the hands of another artist, the scale of the project might seem like a gimmick. But Zhang’s visible attachment to the emblems of his culture make it clear that his large works are grand statements informed by sheer exuberance.

A day that began with a relaxing talk in the artist’s intimate office is about to finish with a flourish. He opens his umbrella, and we wade through pools of rainwater into the largest workshop yet. The scene unfolds like a Terry Gilliam fantasy: The blackened Chinese Warrior, some two stories high, emerges from a fog of smoke, streams of which rise from his enormous breastplate. The hulking statue is covered entirely with ash from incense burned at temples in and around Shanghai. Zhang walks around the back of the armored figure to a small metal door. The source of the smoke turns out to be a pail of incense sticks burning vigorously inside his belly.

No matter what he produces in the future, Zhang’s hauntingly beautiful ash paintings and sculptures will probably define him as an artist as much as the toilet performance in Beijing 13 years ago. “I created a new genre, a new phenomenon,” he says. “There are so many different ways to use ash; I probably won’t lose interest in it for a while. It moves me the most—it’s able to seep through me. What’s left in it are the remnants of so many souls.”

Pointing to several dozen bins, buckets and barrels of the ash clustered in one area of the workshop, Zhang explains that different kinds of incense, used during prayers, produce different colors and grades of residue. The nuances of gray tones and texture, from fine dust to flakes and even entire sections of incense sticks, create wonderfully vibrant surfaces that tempt the viewer to touch them. But working with ash poses a logistical problem: It can’t be flicked onto an upright surface. So the canvases instead lie on the warehouse floor, and the artist’s assistants lean over or sit above them on elongated dollies, dipping brushes into what look like oversize pillboxes—the ash painter’s palette.

Resting against the wall in the back is Zhang’s largest ash painting to date, a 35-by-9-foot epic depicting hundreds of workers creating a channel to bring water to the interior of China as part of the midcentury Great Leap Forward. “China right now is going through something like this. People are showing tremendous ability to overcome nature and do the impossible,” Zhang says. “Back in those days, it was done for survival. Now it’s for affluence.” The artist says he’s had collectors interested in the piece, but “it is for a museum only.”

The theme of challenge resonates with Zhang. He is used to—indeed disposed to—pushing the limits, often with little, if any, public display of emotion. His stoicism falls away, however, as he recalls an event that took place this past summer, during his monthlong journey on the Silk Road in China.

He and a friend were driving through the mountains when they encountered a sandstorm. Rocks were falling, they couldn’t see, and they had just passed a sign saying something to the effect of “Proceed at your own risk—you may die.” He thought that this might be the end. Then a smattering of village lights emerged from the darkness. Zhang’s face glows at the memory. “When you’re driving through the mountains, you meet challenge after challenge,” he says. “But then, after a while, you see the light.” |